20+ SAMPLE Incident/Accident Analysis

-

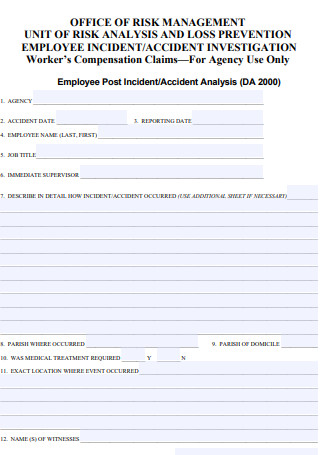

Employee Post Incident Accident Analysis

download now -

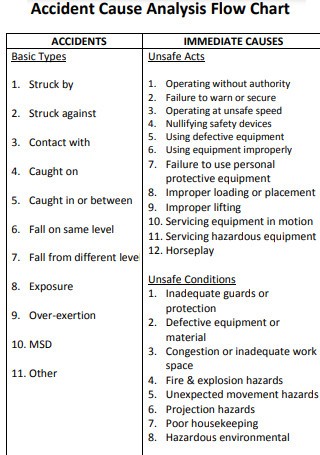

Accident Cause Analysis

download now -

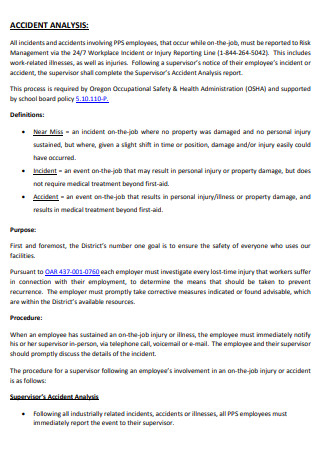

Accident and Operational Safety Analysis

download now -

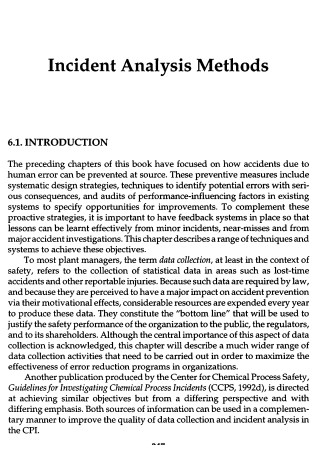

Accident Incident Analysis Methods

download now -

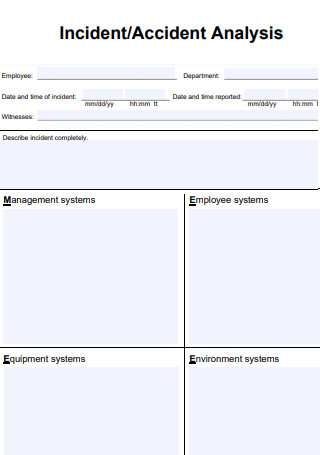

Incident Accident Analysis

download now -

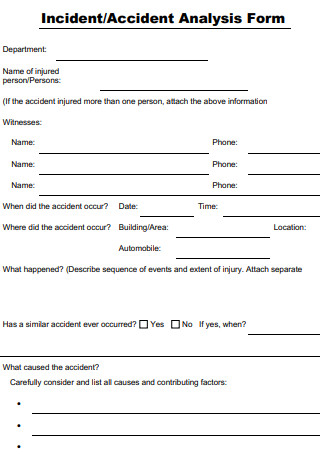

Incident Accident Analysis Form

download now -

Incident Accident Investigation Analysis

download now -

Employee Incident Accident Analysis

download now -

Incident Accident Root Cause Analysis

download now -

Sample Incident Accident Analysis

download now -

Trdaitional Approach Accident Analysis

download now -

Simple Incident Accident Analysis

download now -

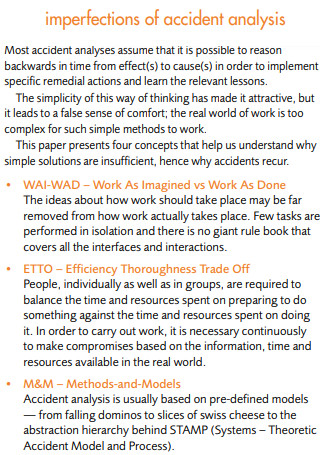

Imperfections of Accident Analysis

download now -

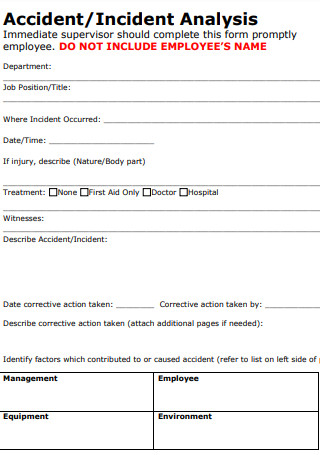

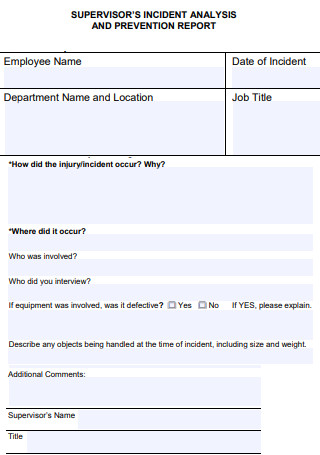

Supervisor Incident Analysis

download now -

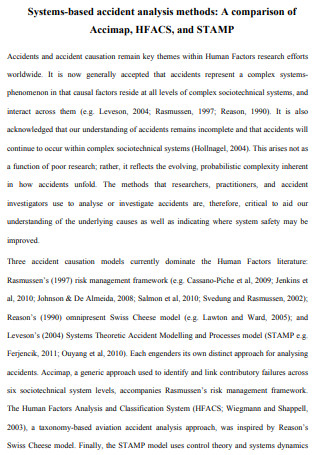

Systems Based Accident Analysis Methods

download now -

Accident Analysis Method

download now -

In Flight Accident Analysis Report

download now -

Risk Assessment Incident/Accident Analysis

download now -

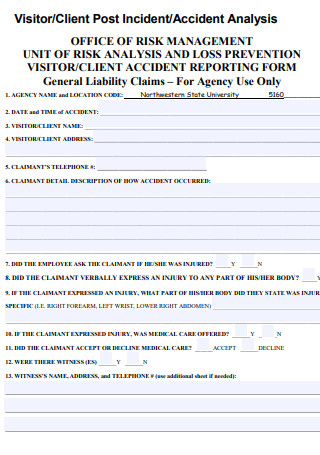

Client Post Incident/Accident Analysis

download now -

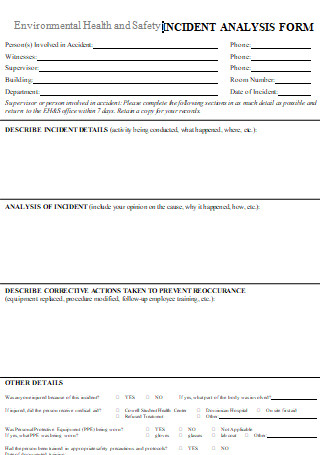

Health and Safety Incident/Accident Analysis

download now -

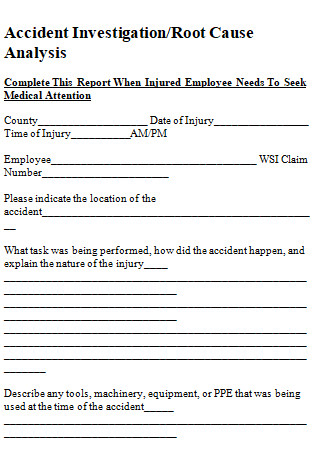

Incident/Accident Investigation Root Cause Analysis

download now

FREE Incident/Accident Analysis s to Download

20+ SAMPLE Incident/Accident Analysis

What Is an Accident/Incident Analysis?

What Are Accidents/Incidents?

10 Tips for the Accident/Incident Analysis:

4-Step Process for Accident/Incident Analysis:

FAQs

Who does the accident investigating?

Why look for the root cause?

How are the facts collected?

What Is an Accident/Incident Analysis?

After an accident occurrence, an accident analysis is conducted to expose the proximate and enabling causal factors so that measures can be identified and applied to prevent a recurrence. The method normally involves the systematic collection, documentation, and communication of relevant information. In addition, an accident analysis is also referred to as an accident investigation.

The term incident is used in some situations and jurisdictions to cover both an accident and incident. It is argued that the word accident implies that the event was related to fate or chance. When the root cause is determined, it is generally found that many events were foreseeable and could have been prevented if the right actions were taken—making the event not one of fate or chance (thus, the word incident is used). For simplicity, we will use the term accident to mean all kinds of events.

What Are Accidents/Incidents?

Accidents are defined as unintentional events that result in injury, illness, or material loss. Safety experts regard accidents and incidents as preventable events that specify correctable deficiencies in an organization’s safety and loss-control system.

Accidents almost never have just one cause but are the result of chains of events and circumstances. An accident analysis falls into the following types:

- Causal analysis

- Expert analysis

- Organizational analysis

Following the outcome of an accident analysis, the authorities may review the existing safety policy, update risk assessment or controls, and update the safety statement for the organization.

10 Tips for the Accident/Incident Analysis:

4-Step Process for Accident/Incident Analysis:

There are four primary tasks linked with incident analysis and reporting. An investigator should have a good understanding of the process and the steps involved in conducting a formal analysis. The process is broken down as follows:

Step 1: Respond. Secure the scene by keeping personnel from entering areas with structural damage, fire, flooding, and damage to machinery or equipment, i.e., pressurized vessel equipment, equipment with stored energy, electrical malfunctions, and process safety issues. After checking the scene for safety, check anyone who appears to be injured and tend to their medical needs. Make sure it is safe to enter the area. Initiate the location emergency response plan if needed.

An analyst’s main goal is to begin gathering incident information that can give critical clues into the causes connected with the incident. Priorities for scene securement include:

- Checking the scene for safety

- Initiate the location emergency response plan

- Provide medical care/transport for injured

- Beware of confirmation bias

- Control existing hazards

- Prevent further injuries

- Get more help if needed

- Preserve evidence

- How you react when informed of an incident matters a great deal

- Respond with empathy and understanding

Access to the incident site should be limited to preserve evidence. Names and numbers of witnesses should be recorded for future use. Taking away witnesses from the incident area and separating them from each other is also beneficial. This allows witnesses to provide their account of events rather than compare stories. The incident site should be secured with some type of barricade or taped off to limit access and avoid adverse exposure to the scene. Any high-value or critical equipment should be secured during the analysis process.

Step 2: Examine. The analysis should start as soon as practical. Do not allow the process to take precedent over attending to the injured parties or property/equipment preservation needs. The point of the analysis is to learn from errors and prevent a recurrence. Should official learning fail to occur, one can reasonably expect the risk factors to remain and undesirable outcomes to repeat. Several tools and techniques can be used in this step to assist in collecting pertinent facts about the incident to determine:

- Cause of injury including hazardous conditions and unsafe worker/management behaviors that produced or contributed to the loss

- Include injured parties in the analysis as they have firsthand knowledge of how the incident occurred

- Analyze the situation, not the person

- Gather factual evidence

- Capture photographic evidence of the scene to assist in “painting a picture”

- Variances—look to identify system weaknesses that produced the causes for the incident.

Vital items to document include the date, time, weather conditions, identification and location of injured parties or damaged equipment, along with witnesses and the sequence of events.

Step 3: Analyze. Analysts should realize there is hardly a single cause for how or why an incident occurs. More likely there is a chain of events, interactions, and factors that lead to causation. Working through all the data may be frustrating when attempting to create mitigation strategies but it’s important to provide the greatest number of useful solutions. The cause of injury describes the harmful transfer of energy. This may take the form of:

- Acoustic – excessive noise and vibration

- Chemical – corrosive, toxic, flammable, reactive

- Electrical – low/high voltage, current

- Kinetic – energy transferred from impact

- Mechanical – components that move

- Potential – “stored energy” in objects

- Radiant – ionizing and non-ionizing radiation

- Thermal – excessive heat, extreme cold

The surface causes of an incident could include:

- Specific/unique hazardous conditions and/or unsafe actions

- Directly produce or contribute to the incident

- They may exist/occur at anytime, anywhere and involve anyone

- They may or may not be controlled by management

- If you’re highlighting a person or thing, it’s probably a surface cause

Meanwhile, in multiple causation, there are five steps involved in determining the causes of an incident. These steps include:

- Analyzing the event to classify and describe the direct cause of the incident

- Studying activities from the beginning of the day up to events occurring just before the incident to identify conditions and behaviors that contributed to the incident

- Analyzing conditions and behaviors to determine other specific conditions and behaviors (contributing surface causes) that contributed to the incident

- Analyzing the contributing condition and behavior to determine if weaknesses in carrying out safety policies, programs, plan, processes, procedures, and practices (inadequate implementation) exist

- Determining system flaws to determine the underlying design weaknesses

Step 4: Learn. There are multiple steps of cause and effect to be discovered during the analysis process. The analyst is given the opportunity through the discovery of the chain of events to create a holistic view of the loss and a systemic corrective action approach. The role of the analyst is to help the organization learn from the event, implement the appropriate corrective actions to break the chain of events, control various interactions, and prevent a recurrence. A systemic approach is likely to develop multiple corrective actions.

After finishing the incident analysis, the next step is to recommend corrective actions and discuss lessons learned. Corrective actions could be related to the ladder of controls as follows:

Engineering controls. Engineering controls consist of substitution, isolation, ventilation, and equipment modification. These controls focus on the source of the hazard, unlike other types of controls that generally focus on the people or items exposed to the hazard. The basic concept behind engineering controls is that—to the extent feasible—the work environment and the job itself should be designed to eliminate or suggestively reduce exposure to hazard.

Management controls. Reduce frequency and duration of exposure to hazards by controlling processes. Management controls may result in a decrease of risk through methods such as changing procedures, improving equipment utilized, or adjusting the work station or environment. The use of personal protective equipment is not considered a means of management control. Four primary strategies for management controls are:

- Safe procedures and practices

- Improved tools

- Scheduling

- Interim measures; improvement strategies to fix the system

Personal protective equipment (PPE). Personal protective equipment creates a temporary barrier from exposure, but it is not as effective or enduring as engineering controls. For example, a maintenance shop might operate older but still functional tools, which exceed the permissible exposure limits for noise. The company can control the exposure through a hearing conservation program with required hearing protection, but this still doesn’t eliminate the noise, rather it only provides a barrier to the exposure.

Interim measures. Interim measures should be initiated to eliminate hazards until a more perpetual solution can be arranged. For example, if a broken electrical outlet cannot be repaired instantly, locking and tagging out the breaker is a reasonable temporary quick-fix until a qualified electrician can be contracted to repair the fixture.

FAQs

Who does the accident investigating?

An investigation would be conducted by someone experienced in investigative techniques, experienced in accident causation, fully knowledgeable of the work processes, procedures, persons, and industrial relations environment of a particular situation.

In most cases, the supervisor should help investigate the event. Other members of the team consist the employees with knowledge of the work; safety officer; health and safety committee; union representative, if applicable; employees with experience in investigations; “outside” expert; and representative from local government.

Why look for the root cause?

An investigator who believes that accidents are caused by unsafe conditions will likely try to uncover conditions as causes. On the other hand, one who believes they are caused by unsafe acts will try to find the human errors that are causes. Thus, it is obligatory to examine some underlying factors in a chain of events that ends in an accident.

How are the facts collected?

Injured workers

The most significant immediate tasks—rescue operations, medical treatment of the injured, and prevention of further injuries—have precedence and others must not interfere with these activities. When these matters are under control, the investigators can start their work.

Physical Evidence

Examine the site for a quick overview, take steps to preserve evidence, and identify all witnesses before attempting to gather information. In some jurisdictions, an accident site must not be bothered without prior approval from appropriate government officials such as the coroner, inspector, or police. Physical evidence is probably the most non-controversial information available.

Eyewitness Accounts

Witnesses should be interviewed alone instead of a group. You may decide to interview a witness at the scene of the accident where it is easier to establish the positions of each person involved and to obtain a description of the events. Conversely, it may be better to carry out interviews in a quiet office where there will be fewer distractions. The decision may depend in part on the nature of the accident and the mental state of the witnesses.

Interviewing

Interviewing is an art that cannot be given justice in a brief document such as this, but a few dos and don’ts can be mentioned. The purpose of the interview is to create an understanding with the witness and to get his or her own words describing the event:

DOs

- put the witness, who is probably upset, at ease

- emphasize the real reason for the investigation, to determine what happened and why

- let the witness talk, listen

- confirm that you have the statement correct

- try to sense any underlying feelings of the witness

- make short notes or ask someone else on the team to take them during the interview

- ask if it is okay to record the interview, if you are doing so

- end on a positive note

DON’Ts

- intimidate the witness

- interrupt

- prompt

- ask leading questions

- show your own emotions

- jump into conclusions

Generally, final step is to come up with a set of well-considered recommendations intended to prevent recurrences of similar accidents. Once you are knowledgeable about the work processes involved and the overall situation in an organization, it should not be too difficult to come up with realistic recommendations. Don’t forget to communicate your findings with workers, supervisors and management. Present information ‘in context’ so everyone understands how the accident occurred and the actions in place to prevent it from happening again.